Martin Luther

Martin Luther, leader of the German Reformation, was a gifted tenor, flutist, lutenist, poet, and composer (Schalk, 19 – 20). He admired and extensively used polyphonic music from the Netherlands, particularly that of Josquin des Pres (Bainton, 268) (Grout, 214). Luther personally composed and arranged at least 10 chorales (Bainton, 266-267). When singing with friends, he would find errors in the counterpoint, which he would correct (Nettl, 61).

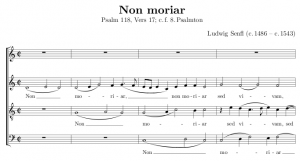

Music had a tremendous personal impact in his life. While under the ban of the Holy Roman Emperor and excommunicated by Pope Leo X, Luther had to stay in the castle of Coburg, while his patron, Prince Elector Johann of Saxony, went to the Diet at Augsburg to defend a confession of faith.  In his room, Luther became very depressed and believed his end was near. In this state, Luther sent a letter to a friend, the famous German composer Ludwig Senfl, asking that he send him a polyphonic version of a favorite antiphon, In pace in id ipsum. Senfl did not send that song until later, perhaps because he had yet to write it, but he immediately sent Luther a copy of his motet on the 17th verse of the 118th Psalm: Non moriar sed vivam (I will not die, but live and declare the works of the Lord). The text and music had an incredible effect on Luther. He wrote those words on the wall of his room and came back to the fight with a renewed spirit (Nettl, 21-25). Luther later arranged Non moriar himself as a motet (Nettl, 60).

In his room, Luther became very depressed and believed his end was near. In this state, Luther sent a letter to a friend, the famous German composer Ludwig Senfl, asking that he send him a polyphonic version of a favorite antiphon, In pace in id ipsum. Senfl did not send that song until later, perhaps because he had yet to write it, but he immediately sent Luther a copy of his motet on the 17th verse of the 118th Psalm: Non moriar sed vivam (I will not die, but live and declare the works of the Lord). The text and music had an incredible effect on Luther. He wrote those words on the wall of his room and came back to the fight with a renewed spirit (Nettl, 21-25). Luther later arranged Non moriar himself as a motet (Nettl, 60).

Surrounded by music from an early age (Schalk, 9), Luther grew up in Thuringia, Germany, which was well known for its music (Nettl, 7). As a schoolboy, he learned Latin and music, and, along with the other students, was required to sing at all of the church services. They learned hymns, versicles, responses, and Psalms, and studied music theory, including the church modes (Schalk, 12). At the age of 15, Luther joined one of the school choirs, the Kurrende, under the direction of a prefect. They went house to house, sang, and begged for alms. They also sang at the weddings and funerals of rich burghers for a small stipend (Schalk, 14). Luther proved in school to be very eloquent and capable of writing high quality poetry (Schalk, 14). Later he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Erfurt (Schalk, 15). On July 17, 1505, Luther joined the monastery of the Augustinians, who were well known for their cultivation of music and how they prized the Psalms (Schalk, 16). Two years later, he sang his first mass (Schalk, 15-16).

Luther struggled fiercely with his conscience, seeing God only as an angry judge who must be pacified by good works. He realised that he could never live up to the requirements of God’s law. Luther believed that to be forgiven, he must confess; to confess, he must recall; to recall, he must be aware of his sin at the time of commission (Bainton, 42). He started to despair of forgiveness. His superior in the monastery sent him to the Scriptures for study, particularly the New Testament. And while preparing lectures on Romans, he found the answer:

I greatly longed to understand Paul’s epistle to the Romans and nothing stood in the way but that one expression, “the justice of God,” because I took it to mean that justice whereby God is just and deals justly in punishing the unjust. My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him. Therefore I did not love a just and angry God, but rather hated and murmured against Him. Yet, I clung to the dear Paul and had a great yearning to know what he meant.

Night and day I pondered until I saw the connection between the justice of God and the statement that “the just shall live by his faith.” Then I grasped that the justice of God is that righteousness by which through grace and sheer mercy God justifies us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise. The whole of Scripture took on a new meaning, and whereas before the “justice of God” had filled me with hate, now it became to me inexpressibly sweet in greater love. This passage of Paul became to me a gate to heaven…

If you have a true faith that Christ is your saviour, then at once you have a gracious God, for your faith leads you in and opens up God’s heart and will, that you should see pure grace and overflowing love. This it is to behold God in faith that you should look upon His fatherly, friendly heart, in which there is no anger nor ungraciousness. He who sees God as angry does not see him rightly but looks only on a curtain, as if a dark cloud had been drawn across his face.

(Bainton, 49-50)

Finally at peace with God, Luther realised that many church doctrines were at odds with Scripture. This came to a head when in 1517, in order to raise funds for a new church in Rome, Pope Leo X offered a German bishop, Albert of Brandenberg, another bishopric in exchange for managing the sales of a new indulgence, which supposedly forgave all sins (Bainton, 56). Indulgences were pieces of paper that certified that a certain amount of merit from the saints went to offset the sins of the holder. These had been sold for years, but this particular one overstepped the normal bounds of such usage. Luther was furious that the church would take advantage of the Christian to extort payment for salvation when all he needed was faith in Christ. In response, Luther posted 95 theses or points for debate on the Castle Church’s doors in Wittenberg, where he taught. They were written in Latin and intended only for debate among scholars, but several students translated them into German and spread them among the people of Germany. The sales of the indulgences dropped off significantly, and after several attempts to get Luther to recant, the Pope issued a Papal Bull or decree stating that unless he recanted within 60 days, he would face excommunication. Upon the Bull reaching Luther, he burnt it (Bainton, 59-126).

The church had declared Luther an outlaw, but it was up to the civil authorities to enforce. Luther’s lord, Prince Frederic III, protested that no German could be executed unless tried before his peers. To this end, Emperor Charles V issued a safe conduct to bring Luther to the Diet at Worms.

Under advice from the papal emissaries, Luther was asked two questions, and a simple answer was demanded for both of them. They had collected a large number of Luther’s writings. He was asked if he was the author, to which he quietly said yes. He was then asked if he would recant what he had written. Luther asked for a day to consider. He was granted this and the next day was brought back before the Diet and asked again whether he would recant. He stated that the works were not all of one kind. He said that in some, he had outlined Christian truths so simply that his opponents had admitted their usefulness. If he recanted these, he would be the first to retract works approved by both friends and enemies. In the next group, he had attacked the Popes and their power. He stated that to recant these would be to condone evil practices. In the last group, he had attacked individuals who had opposed his work. In these he admitted that he had spoken too harshly (Bainton, 129-144). He then said that:

Under advice from the papal emissaries, Luther was asked two questions, and a simple answer was demanded for both of them. They had collected a large number of Luther’s writings. He was asked if he was the author, to which he quietly said yes. He was then asked if he would recant what he had written. Luther asked for a day to consider. He was granted this and the next day was brought back before the Diet and asked again whether he would recant. He stated that the works were not all of one kind. He said that in some, he had outlined Christian truths so simply that his opponents had admitted their usefulness. If he recanted these, he would be the first to retract works approved by both friends and enemies. In the next group, he had attacked the Popes and their power. He stated that to recant these would be to condone evil practices. In the last group, he had attacked individuals who had opposed his work. In these he admitted that he had spoken too harshly (Bainton, 129-144). He then said that:

Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason – I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have often contradicted each other – my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise. God help me. Amen.

(Bainton, 144)

The emperor outlawed Luther, but Luther was still protected by Prince Frederic. Luther spent the rest of his life teaching and working to reform the church and cleanse abuses. A large part of this work was to review and rework the Mass and sacred music.

Principles

Luther’s views on music in worship contrasted with the two other prominent religious philosophies of the day. Catholic music reflected the view of the church as an institution separate from and above the congregation. Catholic sacred works were uniform and collectivistic, with very smooth melodic lines and very little sense of rhythm (Nettl, 2). Catholic composers rarely invented their own melodies, but instead took them from extant pieces (Nettl, 2). However, many Catholic works were based on irreligious secular tunes, which the reformers considered distracting from the sacred nature of the Latin text (Nettl, 6).

Two other reformation movements of Luther’s time were the Calvinists lead by John Calvin, and the Zwinglians lead by Ulrich Zwingli. Both considered the arts to be purely secular and banned or strictly regulated their use. Calvin retained only congregational singing (Nettl, 4), and Zwingli forbade music altogether (Schalk, 10)(Nettl, 5). Interestingly, Zwingli was a talented musician. He set two of his own songs to four-part polyphonic music and played almost every instrument (Nettl, 5). Yet, he stood by and encouraged the destruction of church organs by his followers (Nettl, 5).

Unlike the Catholics, Luther viewed music as an expression of faith, a vehicle of prayer and praise (Nettl, 6). Lutheran music represented the people as the Church, rather than the church above the people (Nettl, 4). The minister became a representative of the congregation before God, instead of the congregation before the church (Nettl, 4). As such, Luther taught that music could have a much wider use and variety than previously allowed (Schalk, 10-11). He appreciated the rich Catholic tradition of music in worship, and used it in his own masses (Schalk, 10). The liturgy was revised to remove papal abuses and to enlighten the people. Congregational song (chorales) was cultivated to inspire and instruct (Bainton, 255). Luther understood from personal experience the power of music to move the hearts and minds of the listener (Schalk, 10). He said:

Music is a fair and lovely gift of God which has often wakened and moved me to the joy of preaching. St. Augustine was troubled in conscience whenever he caught himself delighting in music, which he took to be sinful. He was a choice spirit, and were he living today would agree with us. I have no use for cranks who despise music, because it is a gift of God. Music drives away the devil and makes people gay; they forget thereby all wrath, unchastity, arrogance, and the like. Next after theology I give to music the highest place and the greatest honor I would not exchange what little I know of music for something great. Experience proves that next to the Word of God, only music deserves to be extolled as the mistress and governess of the feelings of the human heart. We know that to the devil music is distasteful and sufferable. My heart bubbles up and overflows in response to music, which has so often refreshed me and delivered me from dire plagues.

(Bainton, 266-267)

Luther was the only reformation theologian to unequivocally affirm music as an excellent gift of God to be used in his praise and the proclamation of His word (Schalk, 9).

Mass

Luther’s largest musical work was his revision of the Roman mass. In 1523, he undertook to revise the mass, trying to alter it as little as possible. The goal of the revision was to remove the stated need for human merit. Because it referred to sacrifice, the canon of the mass disappeared and was replaced by an exhortation to receive communion. He restored the Early Church’s emphasis on communion as an act of thanksgiving to God and fellowship with Christ and each other (Bainton, 255-256). The sermon was given a much more prominent place. The Formula Missae et Communionis was released later that year (Nettl, 69-72) in Latin and was intended for the more wealthy churches and festivals (Nettl, 69).

Luther’s experience with plainchant as a cantor made him interested in writing a liturgy in the vernacular, but he considered himself incapable of performing the task of translating (Schalk, 26). However, because the people would not notice the revision of the Latin mass, in 1526, Luther translated it into German (Bainton, 255-256). The biggest change in the liturgy was the music (Bainton, 266). The liturgy contained three primary elements of music: chants intoned by the priest, chorales sung by the choir, and hymns sung by the congregation (Bainton, 266). Johann Walther and Conrad Rupff were asked to come to Wittenberg as advisors in the making of a German mass (Bainton, 268). Walther described it so:

When he, Luther, forty years ago desired to introduce the German mass in Wittenberg, he communicated this wish to the Prince Elector of Saxony and to the late Duke Johann. He urged His Electoral Highness to bring the old singing master, the worthy Conrad Rupff, and me to Wittenberg. At that time he discussed with us the nature of the eight modes, and finally he himself applied the eighth mode to the Epistle and the sixth mode to the Gospel, saying: ‘Christ is a kind Lord, and His Words are sweet; therefore we want to take the sixth mode for the Gospel; and because Paul is a serious apostle we want to arrange the eighth mode for the epistle.’ Luther himself wrote the music for the lessons and the words of the institution of the true blood and body of Christ, sang them to me, and wanted to hear my opinion of it. He kept me for three weeks to note down properly the chants of the Gospels and the Epistles, until the first mass was sung in Wittenberg. I had to attend it and to take a copy of this first mass with me to Torgau. And one sees, hears, and understands at once how the Holy Ghost has been active not only in the authors who composed the Latin hymns and set them to music, but in Herr Luther himself, who now has invented most of the poetry and melody of the German chants. And it can be seen from the German Sanctus how he arranged all the notes to the text with the right accent and concent in masterly fashion. I, at the time, was tempted to ask His Reverence from where he had these pieces and his knowledge; whereupon the dear man laughed at my simplicity. He told me that the poet Virgil had taught him such, he, who is able so artistically to fit his meter and words to the story which he is narrating. All music should be so arranged that its notes are in harmony with the text.

(Nettl, 75-76)

Luther was interested in the music reflecting the language of the text. In his work Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of Images and Sacraments (1525), he said:

I would gladly have a German mass today. I am also occupied with it. But I would very much like it to have a true German character. For to translate the Latin text and retain the Latin tone or notes has my sanction, though it doesn’t sound polished or well done. Both the text and notes, accent, melody, and manner of rendering ought to grow out of the true mother tongue and its inflection, otherwise all of it becomes an imitation, in the manner of apes.

(Schalk, 26 – 27)

Luther was not the first to write and use a German mass, but the others were simple translations of the Latin (Nettl, 73). Luther changed the Latin melismatic chants into German syllabic chants to better reflect the language (Nettl, 78). Parts of the liturgy were now sung by the congregation: the Credo and Sanctus, for example (Bainton, 270). However, Luther was very aware of the rich background of Catholic church music and kept much of it (Grout, 213).

The largest liturgical change of the reformation was taking congregational participation from being merely tolerated to the centerpiece of worship (Schalk, 6). Prior to the reformation, the music of the mass was restricted almost entirely to the celebrant and choir (Bainton, 269), but now the focus of the mass shifted to the proclamation of the word, and the chorale as the embodiment of this (Marshall). Chorales were originally a monophonic, metric, rhymed, strophic poem and melody (Grout, 214). Luther was very interested in congregational music and was willing to write works as models for what he had in mind (Schalk, 25). He was not only concerned with the music, but also with the words, encouraging good poets to write hymn texts (Schalk, 26). Luther frequently used existing melodies for his hymns, but he modified them beyond simple contrafactum because of his special attention to the declamation of the text (Marshall). Use of literary and poetic forms gave his music a strong presence (Marshall). Through his work, Luther set the standard for chorales, such as what topics they would cover and how they would be used (Marshall). When first introduced, children would be taught the hymns in school and scattered among the congregation to lead the singing (Schalk, 82). Luther used specific modes for different categories of hymns. Ionian for hymns of faith, Dorian or Hypodorian for meditative hymns, and Phrygian for repentance (Marshall). German chorales were sometimes used in the Latin mass (Marshall).

The first time that the German mass was performed was the 20th Sunday after Trinity, October 29th, 1524 (Nettl, 73). The overall structure of the mass was left intact, with the ordinary and proper being left mostly unchanged formulaically (Bainton, 255-256). After the German mass was completed, the Latin mass was still performed, considered a more solemn service for feast days (Nettl, 72).

Other Work

Luther worked hard on the behalf of good, trained choirs (Bainton, 269) and insisted that such choirs be supported and funded (Schalk, 24). In a letter to a prince, Luther said:

Kings, princes, and lords must support music: it is indeed fitting and proper that potentates and regents regulate the use and propagation of the fine arts. While some private citizens and common people are willing to finance the cultivation of music and love it, they are not able to shoulder its maintenance and cultivation.

(Schalk, 24)

In 1524, Luther published a hymnal which included twenty-three of his own hymns. Twelve were paraphrases from Latin chant, and six were psalms that had been put into verse (Bainton, 270) Luther taught that musicians, musical organizations, and music itself were institutions which glorified God, and to not support them would be to squander His gift to mankind (Schalk, 25). Luther was also a capable polyphonic composer, publishing a motet on the Latin text Non moriar sed Lazarus in 1545 (Schalk, 28).

Luther’s influence on music cannot be understated. He set the stage for the next 300 years of music. The idea that music as an expression of personal creativity could be pleasing to God opened the door for Bach, Handel, Haydn, and Mendelssohn (Nettl, 19). He was the only reformation leader that treasured and encouraged the arts as a reflection of the creative ability granted to people by their Creator, and as such pleasing to Him.

Bibliography

Schalk, Carl F. 1988. Luther on Music: Paradigms of Praise. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House

Nettl, Paul. 1948. Luther and Music. Philadelphia: The Muhlenberg Press

Bainton, Roland H. Here I stand: A Life of Martin Luther. Nashville: Abingdon Press

Grout, Donald J. A History of Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton and Company

Robert L. Marshall and Robin A. Leaver. “Chorale.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 8 Dec. 2009 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/05652>.

Robin A. Leaver. “Luther, Martin.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 8 Dec. 2009 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/17219>.

Other sources:

Luther in 1533 by Lucas Cranach: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Luther46c.jpg

Non moriar sed vivam by Ludwig Senfl. Score from: http://www.icking-music-archive.org/scores/senfl/nonmoriar.pdf

Luther Before the Diet of Worms by Anton von Werner, photogravure after the historicist painting in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diet_of_Worms.jpg

That’s all.

I thought the subject heading would show up. What I meant to say is: It’s Senfl, not Stenfl. That’s all.

Thanks for correcting that!

Request permission to either copy your article into our website (Luther’s World) or we will create a link to your website. Our home base is in New Jersey

Certainly! I’d rather you link, if you don’t mind.

I am wondering if you know Martin Luther’s favorite hymn. A gentleman in our church has asked me if I could find out for him. He believes that it is in v. 53 of the works of Martin Luther on page 263-264.

I learned several things about Martin Luther of which I wasnt previously aware. The upcoming 500th anniversary of the Reformation has enlightened me to many aspects of Luther I hadn’t known before—that he was a tenor who played the flute and the lute, who was the only reformer who embraced music whole-heartedly and used it in the liturgy, the chorale and as a vehicle to educate and inspire. Hearing his compositions performed at the Reformation Day celebration last October has me anticipating playing them myself on the flute in the 500th year celebration.